The evolution of Medicine can be thought of as having 3 major waves in the Human History, and we’re in the middle of a new paradigm shift, a major disruption. This article explains what these 3 major waves are, and how we are quickly shifting from Medicine 2.0 to Medicine 3.0.

When you visit a primary care physician, what is the question he/she’s asking you? I bet that question turns around something like this: “What is the problem / what symptoms do you have / what’s wrong / where does it hurt?”. I would also bet that you may be thinking that this is absolutely normal, and there’s no point in discussing about it, right? Well, not so fast, let’s travel together through the ages, and see how different sets of beliefs have given shape to different waves in Medicine (and what that means for our Healthspan). Peter Attia comes with a very interesting framework to explain all of it, which I would like to share with you in this article.

Medicine 1.0

For a very long time, Humanity lacked any scientific method to study any phenomenon. However, the urge of the Human Brain to find explanations for anything and everything led people to invent all sorts of superstitious or in any case scientifically unproven ways of dealing with the unknown. When it comes to human health, even when doctors tried to apply the scientific method, the complexity of the human body was just too high for them to uncover its mysteries, and they just lacked the technological tools to help them really understand what’s going on.

This is how all sorts of ominous “medical treatments” have appeared through History, and how they persisted through entire centuries or even millennia. Here are 2 of the most popular examples :

– trepanning. Trepanning consists in creating a hole in a patient’s skull. When people had various conditions, such as repetitive headaches, or mental disorders, trepanning was thought to allow evil to get out of someone’s head. No need to say that this was based on superstition and false science, but surprisingly, it worked in some situations, because it indeed decreases the pressure in the skull, which in some specific but rare cases can indeed yield some positive results.

-bloodletting. Bloodletting consists in letting a portion of a patient’s blood to spill out of the body. It was believed to heal many diseases. Similarly as with trepanning, this indeed may be appropriate in some very specific situations, but in the vast majority of cases, it was not only useless, but even very harmful to the patients, by weakening them in the very moment when they needed the most resources from their bodies.

Overall, Medicine 1.0 has been the norm until the 19th Century, and was characterized by chaotic cause to consequence associations, which led to catastrophic measures, often worsening the situation of the patients.

Medicine 2.0

It’s only in the late 19th Century, arguably with the work of Louis Pasteur, that Medicine shifted to a new paradigm. He discovered the Rabies vaccine in 1885, and Medicine changed profoundly after that, thanks to the discovery of vaccines of course, but also and most importantly thanks to the wide use of rigorous science and technological tools to study the human body and its diseases.

Medicine 2.0 tremendously improved public health, and let to incredible discoveries which led to a considerable increase in average lifespan :

– hygiene. Scientists discovered that very small life forms, such as bacteria and viruses, were responsible for a great number of diseases and infections, which could be avoided by simply washing one’s hands.

– vaccines. After the Ravies Vaccine, which turned Pasteur into an all-time international star, many other vaccines were discovered, driving to the almost-elimination of some very common diseases (smallpox, polio, etc …).

– antibiotics. Antibiotics were discovered in 1928 (penicillin), and this pave the way to many other categories of antibiotics being discovered since then. Today, there are more than 100 antibiotics.

Overall, in 2023, we still are in this Medicine 2.0 paradigm, which is characterized by :

-a scientific method which allows to assess, analyse, and treat different conditions. The most sophisticated and strong tool to do this is the “double blind clinical trial”, which proves the efficiency of a treatment beyond any reasonable possible doubt.

-an identified symptom/disease, that affects the patient, and can be easily diagnosed. This is very important, because Medicine 2.0 starts with a well identified problem, that threatens the health of a patient in such a way that it makes it easily identifiable, and places some level of urgency on the treatment to apply.

-a short-term cause-to-consequence relationship between the treatment and any possible positive results, which would put the patient into remission. The notion of “short-term cause-to-consequence relationship” is very important, because it emphasises the advantage but also the limitations of Medicine 2.0. It knows how to deal with relatively impactful diseases, when they can be healed by relatively impactful (and quick) treatments.

A great way to see Medicine 2.0 is to imagine a garage that will indeed repair your car, but with huge limitations as very few of the pieces of your car are replaceable, most of the other parts of your car are used beyond repair, and without doing any maintenance neither (only repair with limitations when something is broken). If you car is already old, the repair will tend to be pretty rudimentary, and will only give your vehicle a short additional lifespan before the next time it gets broken again.

Medicine 3.0

This is where things start to get interesting. Medicine 2.0 was a great way to introduce science into the field of human health. It helped us make a huge leap ahead, allowing us to do marvels when it comes to “quick death” (quick death is a shortcut for those situations where a sudden accident threatens the life of a healthy individual, such as for example a car accident, or an arm being cut and then being put back again by surgeons, or people being stabbed or shot, etc …). However, when it comes to “slow death”, that is chronic diseases (a.k.a. neuro-degenerative diseases, metabolic syndrome, cancer, cardio-vascular diseases), Medicine 2.0 is very limited. This happens because of the following reasons:

– chronic diseases start very early in life, and take decades before showing up. Medicine 2.0 does not know how to study such a long-term evolution.

-because of the differences between humans, and the complexity of the human body, very few treatments work for everyone. Most of the time, some treatment will work for a patient, and not for another one. Medicine 2.0 does not deal well with this personnalisation of the treatments, because the double blind medical trials, mandatory to bring a new drug on the market, are very difficult to apply (if not outward impossible) if we take into account that each patient is significantly different from another one.

Medicine 3.0 is the new wave which is coming as I write this article, to stack on top of Medicine 2.0, and bring a whole new standard of care to the whole world:

-the starting point for Medicine 3.0 is NOT a patient that is sick and needs to heal, but a patient that is in good health and wants to stay so for as long as possible. This is a profoundly different mindset for doctors to have!

-prediction and prevention. Medicine 3.0 understands that each individual’s DNA and lifestyle is a great starting point to predict and ultimately prevent some genetic and epigenetic risk factors. It therefore links causes to far-reaching consequences (for example, having a 2 x e4 alleles of the APOE gene, and not taking aggresive preventive measures to lower one’s lipid profile, increases tenfold the risk of suffering from neuro-degenerative diseases in 40 years from now).

-personnalization. Medicine 3.0 takes advantage of the last technological advances, and allows patients to gather huge amounts of data about their body, their biomarkers and their health in general, which was impossible before (for example, glucose used to be measured only during fasting, at a certain point in time. Only recently do we have CGMs to measure one’s glucose levels in real time). The treatments and preventive measures are also highly personnalised, starting from the premise that a trial and error process is possible before we find the best treatment for a patient. This data is then analized in the patient’s interest, allowing him and his doctors assess how efficient that treatment is. We’re relying less on population averages, and cohort analysis, and more on the specific use case of an identified patient.

Wrap up

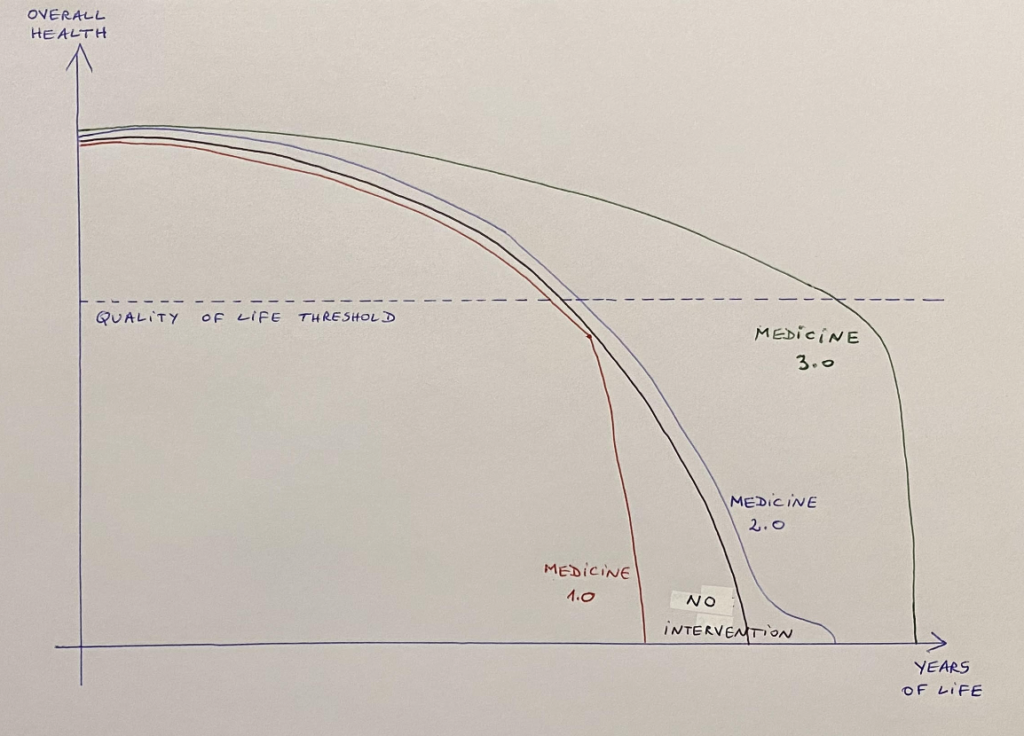

Do you believe in this adage, that “a picture is worth 1000 words”? If you don’t, you will certainly change your mind when you’ll see the diagram I’ve designed for you to summarise the essence of Medicine 1.0 vs 2.0 vs 3.0.

Above, you have the average evolution of human health, as years pass by, moving us from birth to the inevitable decline and end of our lives. You can see that there’s a “quality of life threshold”, that is a level of overall health below which life is not worth living for (it may mean for example that you’re living but you’re paralysed, or you can’t take care of yourself, or you have Alzheimer’s and you can’t think straight anymore – overall, below the “quality of life threshold”, life is not worth living for anymore). You can easily see that as we age, our overall health decreases, and eventually reaches the “quality of life threshold”. Our purpose is to act in such a way, that our overall health stays above that “quality of life threshold” as long as possible (for HS100 members, that is at least 100 years old, if not more!).

Well, now that you understand the diagram, let’s study the different lines:

-the red line is the “Medicine 1.0” standard of care: basically people got sick, and when that happened, instead of having positive treatments that would improve their health, they would have trepanning and bloodletting, basically worsening their situations, and accelerating the decline of their health. Not cool.

-the black line is the “No Intervention” at all. That means that when people got sick, basically not doing anything, and letting the human body use its incredible resources to heal itself, was still better than “Medicine 1.0”.

-the blue line is “Medicine 2.0”. This is where we stand right now. Our life gets incrementally better than “no treatment at all”, because even though accidents are somewhat rare in our modern societies (gun wounds, car accidents, etc …), in the eventuality where you suffer such an unfortunate even, you’ll have HUGE chances of survival and remission, when compared to Medicine 1.0 or “no treatment”. However, Medicine 2.0 fails miserably to improve our Healthspan when it comes to chronic diseases. It just isn’t designed to fix these. So what is does instead, is to use infinite amounts of money to keep patients alive for a couple of additional years, but in a very poor general health condition, most often leaving them without any joy of living. This is why you see an inflection of the blue “Medicine 2.0” curve toward the extreme right of it, before intersecting 0, which is the end of life.

-finally, the best curve is obviously the green one, “Medicine 3.0”, where 3P measures (Preventive, Predictive and Personnalised) allow patients to take care of their long term health long before they feel any symptoms of any disease, carefully monitoring decades ahead how their biomarkers evolve over time. This data allows Medicine 3.0 to design efficient measures with long-term positive effects, helping patients stay healthy as long as possible. An interesting side-effect of this approach is that it allows to always focus on the “limiting factor”, ans as such, to increase healthspan, but also generate what is called “compressed morbidity”, which means that the amount of time where people are alive but impaired is much shorter than for the other alternatives.

So my dream is that soon enough, instead of “Medicine 2.0” doctors asking you “what problem do you have” when we start a medical consultation, the doctor will tell you “When I look at your biomarkers, I see you’re in good health, congratulations! Let’s work at keeping it that way for another 40 years!”.